Rebel

governance concepts & mapping Sagaing’s local governance

Research / Theory

Rebel Governance

Institutions

There is a relatively rich literature on rebel governance. It is

clear (perhaps obvious) that rebels are often aspiring states, who

provide order to populations. However, theorizing both the causal

processes and the types of institutions remains a major area of inquiry.

There are three main actors: rebels, civilians, and the incumbent

state.

Arjona’s

Rebelocracy: rebel order, time horizons, and pre-existing

institutions

- In Rebelocracy: Social Order in Colombian Civil War (Arjona 2016)

provides evidence that insurgents provide order to civilians in most

cases. The main determinant of this is the time horizon of

rebels. If short, they do not provide order, but for most, a long-time

horizon is valuable as they need recruits, information, and other

resources.

- Rebels prefer direct control, as it allows

them to…

- gain territorial control

- create institutions which build organizational capacity

- elicit (punish) civilian (non-)cooperation

- Rebelocracy or Aliocracy: Rebel’s ability to

directly govern (rebelocracy) may be curtailed by the desirability of

incumbent institutions and the collective mobilization capacity, which

allow for collective action against the rebels. In these cases, rebels

agree to aliocracy.

- Collective action capability <—-> no collective action

capability

- Desirability of incumbent local institutions <—->

non-desirability (or disagreement over) incumbent local gov

- Ideology does not matter: Arjona argues that

ideology is epiphenomenal. Fundamentally a tool for power (i.e. akin to

a universal profit motive which drives different business strategies).

Rebel groups use whatever ideologies they think will be most effective

for garnering civilian support alongside institutional coherence

Beginning definitions and

concepts:

Rebel governance

- From Arjona, Kasfir, and

Mampilly (2017)

- Rebel governance is governance by a non-incumbent actor claiming a

legitimate role as a future sole government/regime during civil

war.

- From Kasfir pp. 21 in Arjona, Kasfir, and

Mampilly (2017) :

- Organizing civilians for a public purpose when a non-state armed

actor: 1) has territorial control, 2) a residential population, and 3)

violence or threat of violence.

- Kasfir emphasizes the importance of the ‘distance’ between rebels

and civilians, which sets the mode of interaction.

- The aim of rebel governance is varied: civilian encouragement,

civilian administration, organization for material gain (e.g. natural

resource extraction or industry).

Rebel organizations

- Coordinated groups who engage in violence to gain undispured control

over (a portion of) the pre-existing state.

- Rebels are those which involved directly in military action and/or

planning (including logistics and internal organization).

- Providing support external to the organization does not make a

civilian a ‘rebel’ (basically rebels are the army or government analog

of a ‘state’, which includes leaders, administrators, and the army)

Civil war

Though definitions vary, scholars generally agree that a civil war involves a protracted armed conflict that takes place within a recognized sovereignstate between parties subject to a common authority at the onset of fighting [@kalyvas2006logic]. kalyvas2006logic

- This is distinct from similar but distinct (‘cognate’)

phenomena:

- [riots, ethnic conflict not involving the state, domestic terrorism,

coups, genocide, criminal activities]

Necessity of political aim

Rebels have multiple end goals for gaining power. However, the civil

war must ultimately be political, challenging the incumbent state actor

at the beginning of the war.

- Ideologies (religious, economic, ethnic)

- Profit motives

- Power motives

Civilians

are at the heart of winning civil wars. Rebel governance is

optional.

The importance of civilian support has long been realized in civil

war (citing Mao 1963; Guevara 1968; Ahmad 1982; Laqueur 1976).

Civilian support, however, does not necessitate

governance

Civilians are both challenges and opportunities.

They are the ‘other’ actor which rebels and incumbents fight over.

- Provide

- [food, supplies, information, recruits].

- I’d add motivation, social support, and morale for insurgent

groups

- Threaten inverse of each of the above

- [food to enemy, supplies to enemy, information to enemy, recruits to

enemy]

Causal theories have become more materialist and realist

over time: In the introduction of Arjona, Kasfir, and

Mampilly (2017), they state that:

- Earlier work focused on insurgents competing for

civilian support with ideogloy and cultural values, while newer

work has focused on coercion and material incentives.

Establishing new governance is double-edged:

Providing governance seeks to ‘win over’ the population. However, this

process has both risk and reward (double edged):

- By deploying public goods, ideologies, and cultural beliefs, they

can cause the population to more closely identify with rebels

- However, changing existing institutions, norms, and beliefs via

coercion — if viewed as legitimate prior — creates a risk of

backlash.

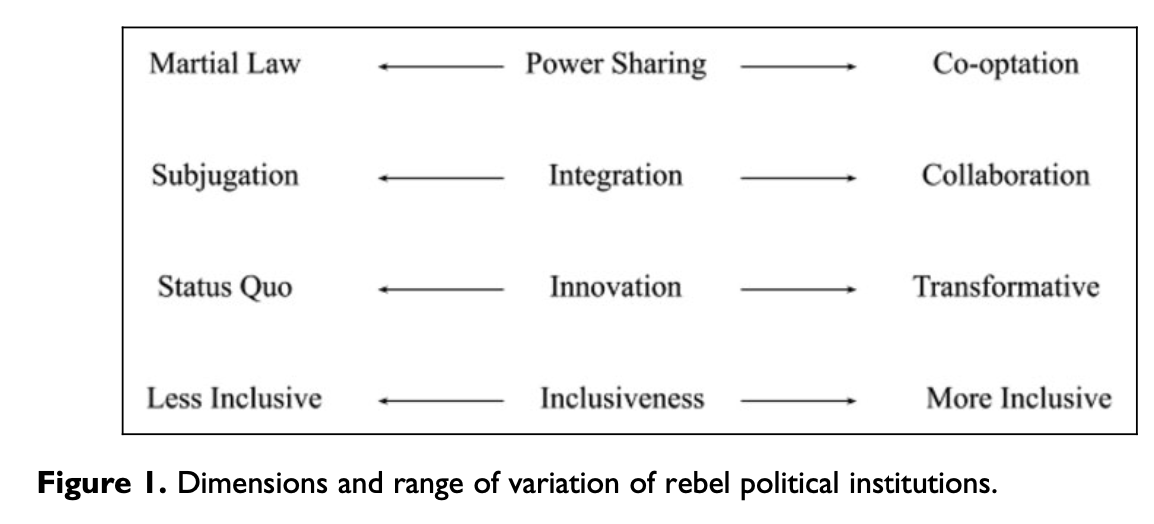

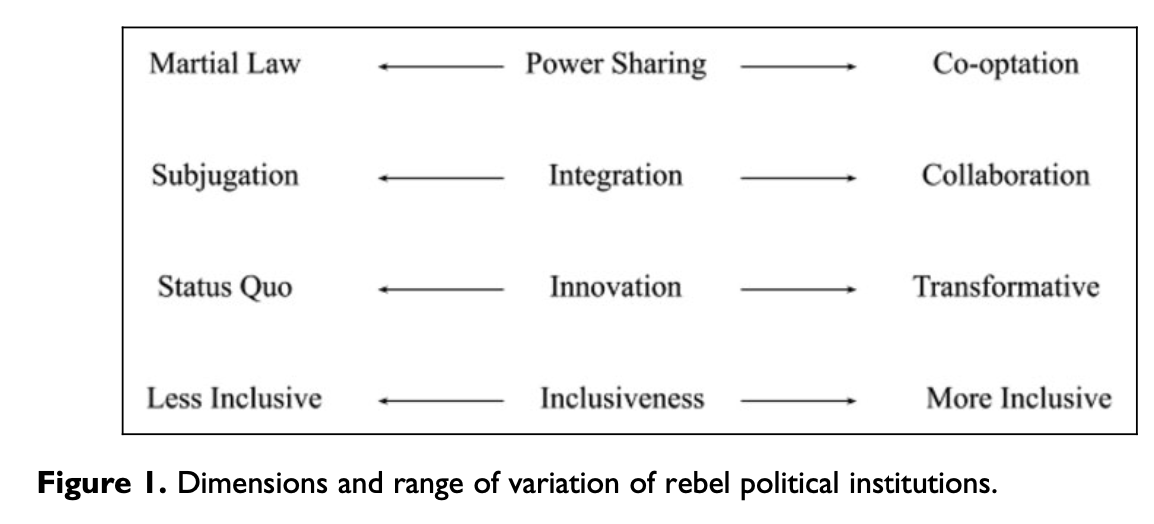

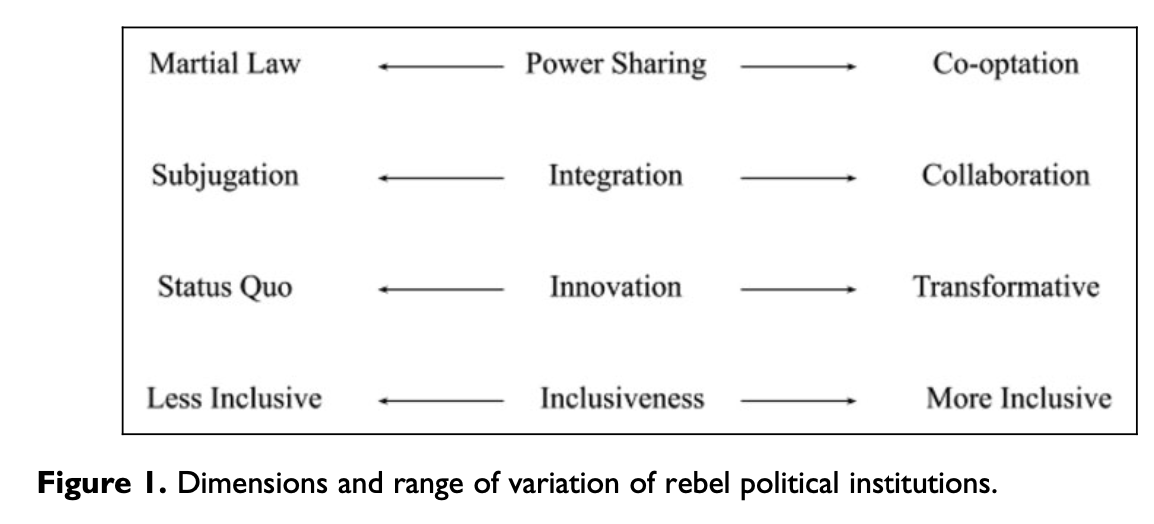

Typology

of rebel political institutions (Mampilly & Stewart 2021)

(Mampilly & Stewart 2021)

provide a typology of rebel governance which goes beyond Arjona,

Kasfir, and Mampilly (2017)‘s single variable spectrum between

rebelocracy and aliocracy. Their typology reduces abstraction by

separating three factors which fall under Arjona’s initial distinction:

power-sharing, integration, and innovation. However, they also add

inclusion (no pun intended). Which adds a ’democratic’ dimension. Their

discussion also expands on the logic behind each. Notably, they

seemingly do not follow Arjona’s rejection of ideology as epiphenomenal.

#### Typology of rebel institutions:

- [power sharing, integration, innovation, inclusion]

- Power sharing: How much power do civilians have?

- military martial law <—–> complete civilian autonomy

- Integration: How ‘hands on’ are rebels in

governance?

- no integration <—–> full collaboration in governance

institutions

- Innovation: Are institutions co-opted or replaced?

- wholesale replace <—–> only co-opt existing

- Inclusion: Both % and identity inclusion

- minimal inclusion <—–> maximal inclusion

Rebel governance as a

stepwise process

Rebel groups make strategic/ideological decisions in a

stepwise fashion

STEP 1: Power-sharing:

Martial law <-> full civilian autonomy

This is a higher-order variable. If there is NO power-sharing,

then the other three are essentially at the minimum (no integration,

wholesale replace, and zero inclusion)

Benefits: full civilian control

Downside: costly (no work via agents) and

unpopular

Logics:

- population is not part of ‘imagined community’

- strong ideological preferences at odds with civilians

- strong, short-term security needs

Integration

of existing institutions: rebel participation in administration

- The degree an insurgent organization places itself within

administration bodies.

- Maximally, the rebel group could have a representatives at each

administrative level (alongside civilian)

- Minimally, the insurgents create boundaries (e.g. no support to

state), but otherwise do not interfere

- Benefits: Draw on legitimacy of pre-existing

institutions, block potential rivals from co-opting

- Downside: somewhat costly to integrate fully

- Logics:

- Less integration due to pre-existing social ties + alignment. If

there is very high trust + social ties between communities and rebels,

then little integration is needed (they can allow them to administrate

within rebel guidelines).

- More integration/co-option is needed when they need to surveil

administration, but do not want to be fully coercive (i.e. don’t want to

impose martial law).

Innovation: replace or

co-opt?

- Does the insurgent organization replace or co-opt?

- This can have both ideological and strategic motivations

- Benefits: Can transform institutions for strategic

or ideological (‘revolutionary’) alignment

- Downside: replacing can generate backlash

- Logics:

- Some groups are ideologically radical (‘revoluationary’), such as

fundamentalist Islamist. These aim to replace/innovate. However, they

may also balance the sequencing of this to be less threatening

(i.e. provide services first, institutional overhaul later).

- Non-revolutionary groups only follow strategic goals. That is, they

aim for resources and popular support.

Inclusion:

power sharing across population and identities

- Fundamentally a democratic principle.

- How ‘included’ are different identities (vertical or horizontal) in

governance processes?

- Includes majoritarian and group/minority concerns – not only how

many but if identities are excluded.

- Benefits: Similarly, both strategic (blocking or

including ethnic outgroups) and ideological (e.g. communists support

women’s inclusion)

- Downside: canonical puzzles of optimal inclusion

among groups for stability

- Logics:

- Some groups are ideologically radical (‘revoluationary’), such as

fundamentalist Islamist. These aim to replace/innovate. However, they

may also balance the sequencing of this to be less threatening

(i.e. provide services first, institutional overhaul later).

- Non-revolutionary groups only follow strategic goals. That is, they

aim for resources and popular support.

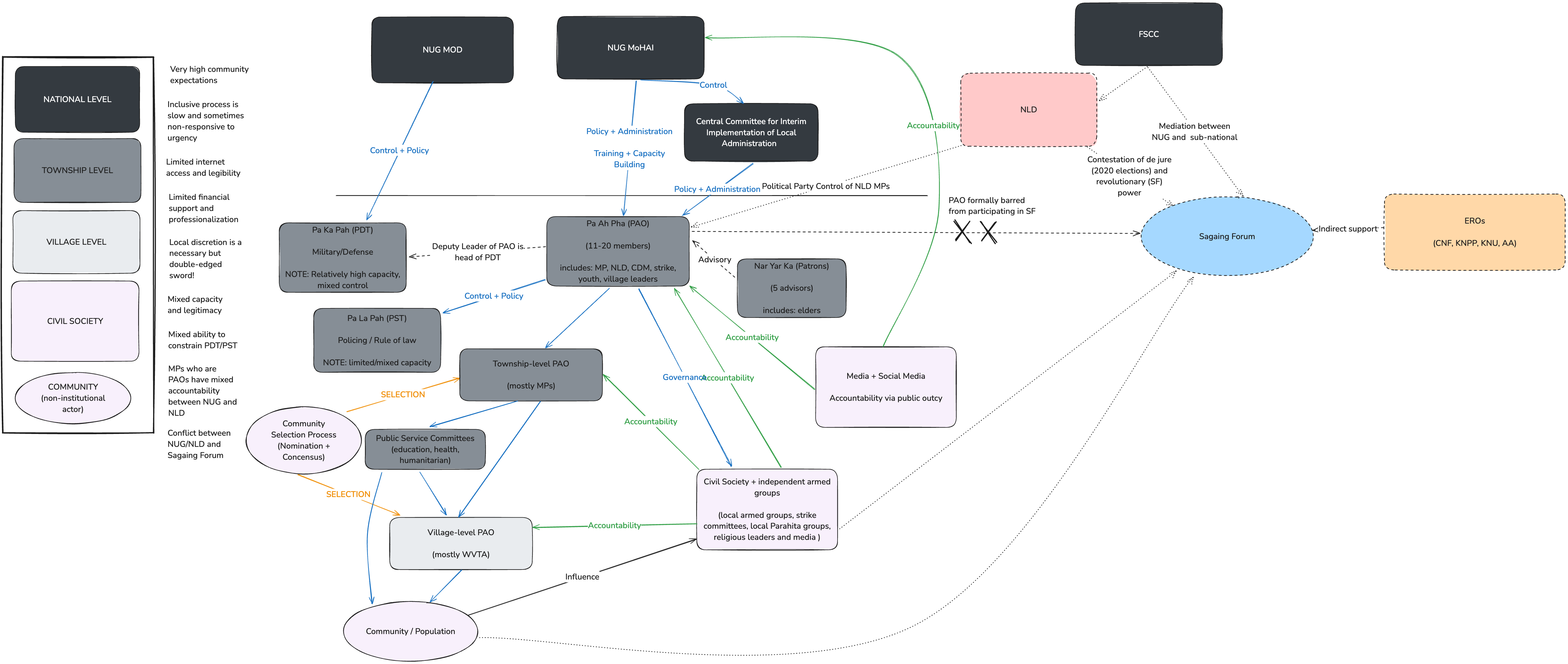

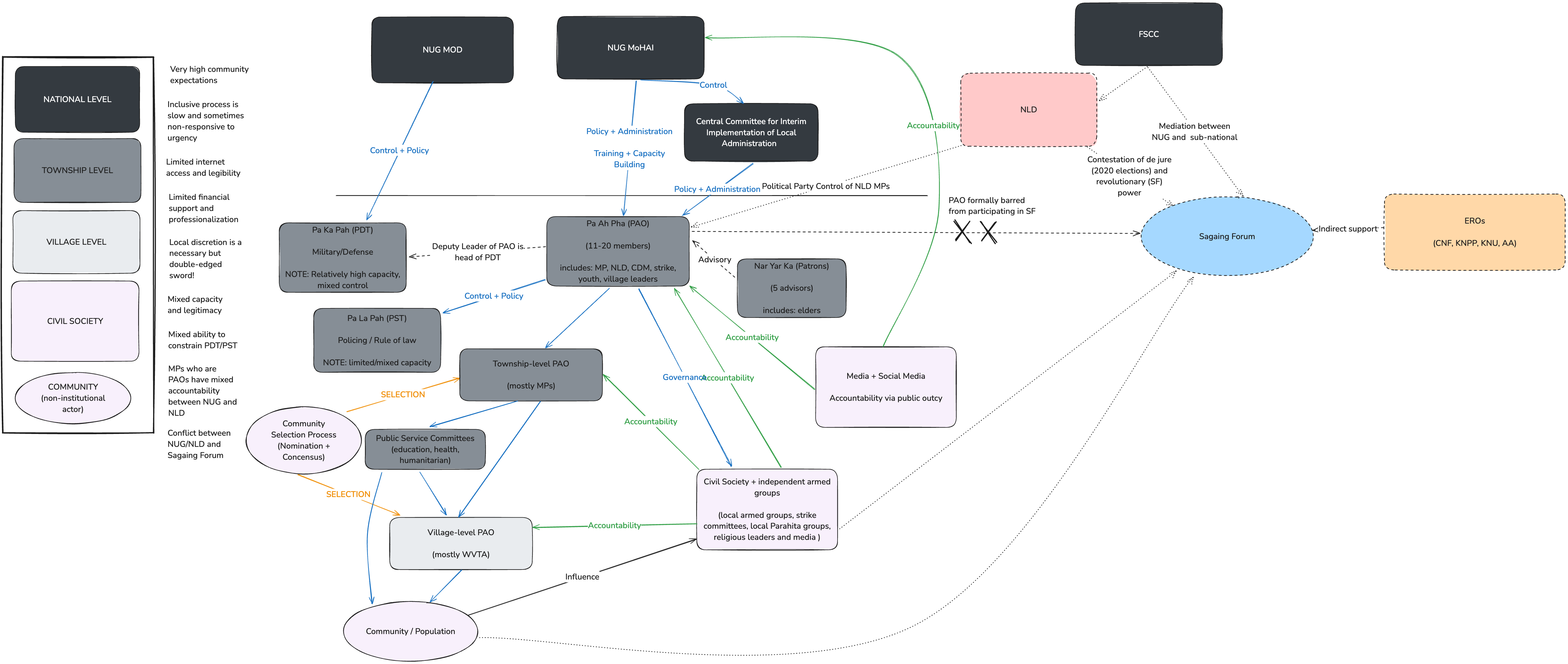

Map of Sagaing Governance

A quick diagram of institutions+actors in Sagaing Region post-coup in

resistance controlled areas (as of Dec 2024)

Arjona, Ana, Nelson Kasfir, and Zachariah Cherian Mampilly, eds. 2017.

Rebel Governance in Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.